Part 1 of of “EME on a Budget” introduces EME and discusses operational basics and propagation. Part 2 discusses essential requirements for an EME station.

This final installment provides an example on how to make your first EME QSO.

Setting up the Software

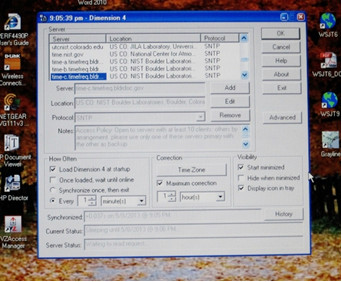

If you’ve never used WSJT software you will need to download it from the Internet and then READ THE MANUAL to familiarize yourself with the screens. You’ll also need to enter your own station parameters into the WSJT program and make sure that the necessary interfaces (serial connection, audio in, audio out, etc.) between the laptop/PC, Rigblaster, and transceiver are correct and functioning as they should. Verify that the Dimension 4 or other “time sync” software is keeping the PC clock corrected to less than a second of error. There are instructions on setting the level of the audio tones that comprise the digital signal fed to the transceiver; follow these instructions carefully, especially the procedures for balancing the tone levels *AND* ensuring that no ALC action takes place as this can distort the transmitted signal and make decoding difficult or impossible at the receiving station.

Since the WSJT manual is rather long and – not to put too fine a point on it – a bit ponderous, I highly recommend that you also download “W7JG’s Additional Tips for Using JT65 in WSJT” which you can find at…

Here you will find clear and concise instructions for how to set the parameters in the JT65 screen for most efficient EME operation.

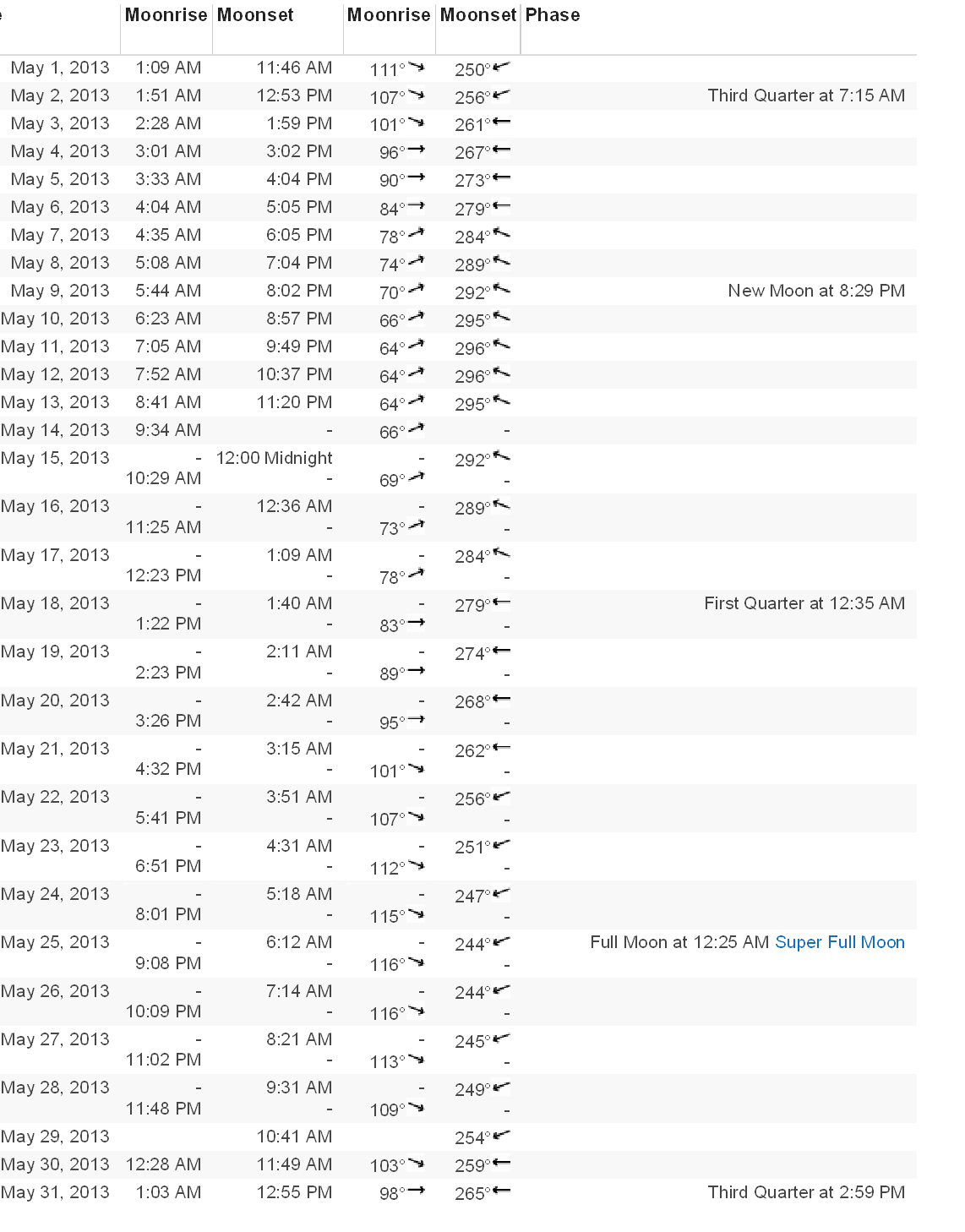

Initially, you should plan to operate only at Moonrise, especially if you have no elevation control on the antenna. You can go to the “timeanddate.com” website at…

…to print a list of the Moonrise times and azimuths for our area (Washington, DC) for the current month. Make sure you choose the “rise/set time/azimuth” display option. The times shown in the table are local time corrected for DST.

Operating and Completing Contacts

Begin your first EME operation by pointing the antenna at the necessary azimuth point specified for Moonrise. WSJT should be set up for 144 MHz and JT65b mode. I usually turn on the transceiver and laptop about an hour before scheduled Moonrise, bring up the WSJT screens, and check that Dimension 4 is controlling time correctly.

Dimension 4 requires that the PC be connected to the Internet continuously to keep the system time accurate.

At this point I carry the amp/preamp and small power supply outside (in the special container shown in the photos of the previous section), make the connections from the shack and to the antenna, and power up the equipment. Then I return to the shack and run a couple of test sequences to check levels on the transceiver, etc. I also walk outside during the “send” portions to make sure that the red transmit LED is glowing on the front of the amplifier and that the power supply meter indicates correct current draw (about 23 amps in my particular case).

Just before the Moon is scheduled to break the horizon I bring up the N0UK JT65 EME-1 chat page (It doesn’t hurt to also check the JT65 EME-2 page just to see which is being currently used) and look to see who may be active, who is calling CQ, etc. Once the Moon rises above the horizon, tune the transceiver to where stations are calling CQ and see if you get any decodes by clicking the MONITOR button on WSJT. Make sure to set your RIT to the “Doppler” offset indicated on the WSJT screen.

If you decode a CQ click the “AUTO ON” button on WSJT but first MAKE SURE that you are transmitting the OPPOSITE time period from the CQing station, i.e., if he’s sending “1st” you should be sending “2nd” and vice-versa. If you decide to try a CQ yourself make sure you alert the users on the chat page by posting something like “CQ 144.120 2nd K4MSG Paul FM19”.

Here is how the correct sequences look for a VALID QSO for two scenarios: Answering a CQ, and someone else answering your CQ.

| Answering a CQ | |

|---|---|

| I decode: | CQ G4SWX JO02 |

| I send: | G4SWX K4MSG FM19 |

| I decode: | K4MSG G4SWX KO03 OOO |

| I send: | RO |

| I decode: | RRR |

| I send: | 73 |

| I decode: | 73 |

| Calling CQ | |

|---|---|

| I send: | CQ K4MSG FM19 |

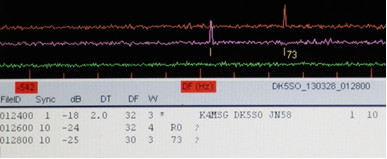

| I decode: | K4MSG DK5SO JN58 |

| I send: | DK5SO K4MSG FM19 OOO |

| I decode: | RO |

| I send: | RRR |

| I decode: | 73 |

| I send: | 73 |

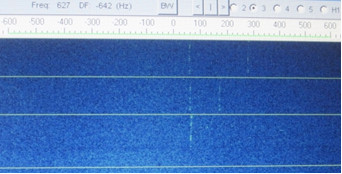

Here is how the above looks in the software…

My CQ prefaced his first transmission and my “OOO” followed it, my “RRR” was sent after his “RO”, and my “73” was sent after his “73”. My transmissions were during the ODD minutes (0123, 0125, etc.).

The lower segment shows the transmission when he called me, the center shows his transmission of “RO”, and the upper shows his transmission of “73”. The last two transmissions are “two-tone” only and easy to identify on the spectrum display.

How successful can a small EME station be?

Although I am a green “newbie” at EME I have been gratified with some success. Despite only operating sporadically I was able to complete 14 EME QSOs in 8 countries over the first couple of months. These contacts were made on different days and under different conditions and indicate that my set-up provides repeatable results WHEN CONDITIONS ARE FAVORABLE. This last caveat is very important because when you are running a single-Yagi, low-power station for EME you cannot expect to successfully achieve two-way communications via the Moon except under the best of conditions.

However, despite the limitations of using a “minimalist” set-up and coping with the vagaries of Lunar propagation I must confess that EME operation can become addictive. Success requires large amounts of patience and a willingness to devote many hours to attempting to make QSOs with no guarantee of success on any given day, but with practice and a commensurate increase in experience, coupled with increased understanding of limitations, will come increased success – and probably a degree of motivation to seek ways to incrementally improve one’s EME operational capability.

You will be operating on the fringes of the ultimate weak-signal challenge for an amateur station and success in making QSOs will place you in a select group of hams.

A future Part 4 will describe a similar set-up and results for small-station EME on 432 MHz. Stay tuned!

Paul Bock, K4MSG, has been licensed since 1957 and holds an Extra Class license. He is currently primarily active on small-station EME but has operated other weak-signal modes on VHF/UHF as well as having been fairly active in HF CW traffic work. Paul is a LM of ARRL and also a member of the A-1 Operator Club, QCWA, CW Operator’s Club and several other ham radio organizations. He has earned DXCC, WAC, and WAS on HF and VUCC on 50 and 144 MHz.

A retired EE who worked in the Defense and Telecommunications fields, Paul is a Life Senior Member of IEEE and co-inventor of a patented telecommunications device. He is also a retired U.S. Navy Master Chief Petty Officer (E-9). He holds commercial radio operator licenses as 2nd Class Radiotelegraph Operator, GMDSS Maintainer, and General Radiotelephone Operator, all with Ship Radar endorsement.

Thank you for these useful posts – I am just beginning to investigate EME, but very excited about the possibilities. Cheers! Robert K4PKM

Everything I wanted to know and nothing superfluous. Thank you!